The image above is actually a combo of two different ones. The guy slashing at the creature in front of him is also from the illustrated lid of the boxed set for the first edition “red box” set for Dungeons and Dragons.

Hello Games, the indie studio that created that cool trailer for their upcoming procedurally generated space exploration game, No Man’s Sky, suffered a bit of a setback in the past week when a flood wrecked their offices along with those of Born Ready Games (Strike Suit Zero).

Born Ready managed to save much of their hardware by being there before leaving on Christmas holiday, but Hello Games had already left when the water unexpectedly hit. Born Ready tried to help but had no access to the office. Still, Hello Games are pretty optimistic in getting back onto their feet and are getting quite a bit of positive support from everyone around.

The idea of procedurally generated games isn’t new, but the applications are always exciting to see especially when the devs flex their creative juices to bring out something really special like No Man’s Sky or when Bethesda put together Daggerfall’s seemingly limitless world. The idea was also used to a large degree by many of the earliest games to both save time on development while tackling the illusion of huge worlds stuffed onto floppy disks from Rogue to Elite.

Rogue’s simple, ASCII dungeons in 1980 were an early example of procedurally generated magic with every visit creating a new world for players to gingerly step their way through. Dying was expected, monsters could be unforgiving, food scarce, and treasures few. But every visit would always bring new dangers as a randomly generated dungeon reshuffled rooms, treasures, and beasties. Later, others would try and develop their own take on the same formula with new enhancements such as 1984’s Hack which introduced shops and pets and eventually led to the popular Nethack in 1987.

A few years later, SSI and Dreamforge dipped their toes into the roguelike arena. With the TSR license under SSI’s belt at the time, making one based on Dungeons & Dragons seemed like the most natural thing to do. It’s almost surprising that it took them a few years to get to that point, but by 1993, they had a few pieces in place in the form of the work Westwood Associates had done on Eye of the Beholder in 1991 and its sequel later in the same year. Though Westwood and SSI parted ways, EoB III came out in 1993 thanks to SSI doing it themselves.

So when Dungeon Hack came out in the same year, it was as if SSI were saying “if you love grid based, first-person dungeon crawling so much, here’s as much as you can handle”. Because that’s what Dungeon Hack was — a limitless smorgasbord of hack ‘n slash dungeon levels.

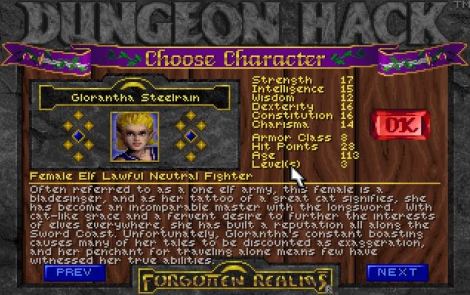

The game boiled the experience down to the bare essentials right after a stirring opening cinematic setting up the basic quest to find an ancient orb by delving into a mysterious dungeon. Then it was off to a stable of pre-made characters, all based on AD&D races and class crunch, or the option to roll up your own with a simplified creation system. Roll up whatever stats you want, tick the race and classes you want, and you’re ready to jump right into a dungeon.

A nice selection of pre-made characters, each with their own biographies, lie in wait to either die or succeed in their endeavors.

Then, it’s time to pick a dungeon difficulty — Easy, Medium, Hard, or Custom. Each one creates a dungeon based on a set of presets. On Easy, for example, there are fewer monsters and more loot. Hard cranks things up with more monsters and even less food to be found.

Picking Custom cracks open page of settings to create the experience you want such as scaling dungeon levels from 10 to 25, enabling multi-level puzzles or not, determining how strong poison is, or whether you want to activate permadeath which will erase any saves associated with your character when they die. CGW’s Scorpia, in her review for the game in 1994, was thankful for the option to toggle undead and enemy spellcasters on or off though not so thankful for the game’s strict adherence to AD&D 2nd edition’s rule of no casting while wearing armor making for exceptionally squishy mages.

Tons of options gave would-be dungeon masters the ability to shape the dungeon of your dreams…or nightmares.

She also noted that maxing out the loot setting didn’t turn it into a “Monty Haul” experience raining gold and valuable relics all over the halls when a monster died. Stuff dropped more often, but high end stuff still kept itself rare. It also had the dangerous tendency to be cursed, something that you might not find out until you put those snazzy new bracers on and discover that it’s time to reload.

Gameplay takes right after the Eye of the Beholder games with a first-person view, grid-based movement, 90 degree turns, a compass, and real-time click combat. Only this time, you’re exploring solo. No party. Just you and your skills. The good news is that you can save in the dungeons, rest up, and keep going. Experience levels are automatically earned as you earn enough for each.

VGA graphics and a few slight tweaks to the engine used in Eye of the Beholder III made Dungeon Hack’s halls and critters look particularly good.

It didn’t have much of a story, but it did do one thing very well — provide a way to delve into a hack ‘n slash crawler boasting “4 billion possible dungeons”. Players could even share the same dungeon between each other if they knew the seed and option numbers needed to recreate it. There was even a leaderboard to compete against yourself with.

Today, like much of SSI’s catalog, it’s buried out there on various abandonware sites ready for emulators like DOSbox to give it new life. It came out for IBM PCs using MS-DOS and also the PC-98 in Japan.

All in all, not a bad game that took the roguelike formula and mashed it together with the graphics and gameplay that FTL’s Dungeon Master and SSI’s Eye of the Beholder series were built around, especially if your sword arm or wizard’s intuition were itching for a little bare bones adventuring without a lot of things to worry about outside of a mini-map, a large inventory, and a set of solid stats.